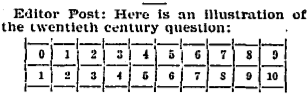

How to Periodize History: 2020 and the Decade Dilemma

on

A new year in the Common Era has arrived, surely to inundate us all with visual acuity puns. But has a new decade also arrived?

The question has percolated through the loud void of social media, reverberating across digital content mills and respectable media outlets alike. We all find ourselves burning with new intensity, searching for any authoritative voice to make sense of this quandary. The New York Times, The Irish Times, India Today, Farmer’s Almanac, Timeanddate.com, please somebody tell us!

Others resort to the nihilistic view that decades never begin or end, or rather, begin and end always and forever — they’re just ten-year spans of time without any defined order between them.1 This perspective was introduced into the public mind recently by Morgan Rielly, a player for the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team:

I don’t think it’s even the end of a decade. Every new year is the end of a decade. 2008 to 2018 [sic] is a decade. 2009 to 2019 [sic] is a decade. Every f—ing one is the end of a decade. So all these people saying the decade’s come to an end — that happens every new year.

So, it’s the end of the century, it’s the end of you-name-it.

The Two Camps of Counting

When asked whether 2020 marks a new decade, people fall into two camps, which I’ll call the Cardinals and the Ordinals.

-

The Cardinals answer yes, for decades are identified by their digit representations. The previous decade, the 2010s, included the years 2010 through 2019, while the new decade, the 2020s, includes the years 2020 through 2029.

-

The Ordinals, on the other hand, answer no, for decades are identified by ordinal numbers counted in sequence from the beginning. The current decade, the 202nd (or the 2nd of the 21st century), includes the years 2011 through 2020, while the next decade, the 203rd, will include the years 2021 through 2030.

These two camps are both so rational and natural that a person in one camp might deny the very existence of the other. Not since “the dress” of 2015 — is that still this decade? — have two camps formed so resolutely online. Are they not both completely legitimate ways to count off the decades? If only some authoritative source could lend its weight to either camp.

In an earlier time, the Pope himself might have served as just such an authority. After all, our calendar isn’t called “Gregorian” for nothing; Pope Gregory XIII commissioned it in the 16th century. Recent articles on the subject have consulted meteorological associations, philosophy professors, and the United States Naval Observatory.

I will put forward two potential authoritative sources on whether decades should be counted according to Cardinals or to Ordinals: ISO 8601 and decennial census legislation. And unfortunately, they lead us into different camps.

In One Corner, the Geeks

ISO 8601 is the specification of (representations of) dates, times, and other calendar entities for use in computing. The International Organization for Standardization defines new versions every so often, the most recent one in 2019. It’s the closest thing we’ve got to a gold standard for dates and times in software. What’s the right way to represent dates? Local times of day? Local times of day for some time zone? Time scales? Leap seconds?

ISO 8601 even defines a new standard calendar adapted from the Gregorian calendar.2 Just as Common Era was a secular substitution for Anno Domini, the ISO 8601 calendar supplants the Gregorian calendar. No more pesky Year 1 C.E. preceded by Year 1 B.C.E.; ISO 8601 has Year Zero,3 and negative years. That essentially makes the Ordinal thinking moot, as the first ISO 8601 decade includes the years 0 through 9, not 1 through 10.

Indeed, decades, as defined in ISO 8601, are the years XXX0 through XXX9.4 For example, using J to denote decades, “the 2020s” are represented as 202J; the “zero decade” is represented as 0J; and “the negative zero decade,” meaning years -9 through 0, is represented as -0J. Somewhat strangely, the latter two decades both include year 0. As a consequence, ISO 8601 really rejects the Ordinals since decades no longer describe an ordered, mutually exclusive sequence of spans of ten years.

ISO 8601 is firmly in the camp of the Cardinals.

that sought input from collegiate experts.](https://typesandtimes.net/assets/img/decade/boston-herald-1899-when-new-century-begins.png)

In the Other Corner, the Wonks

Not everyone finds ISO 8601 to be all that authoritative. But what about nation states? Although they don’t generally have reason to weigh in on the exact definitions of time, they do tend to institutionalize the decade in particular — as the period in which the government conducts a census. For those governments that conduct them decennially, surely they must spell out the precise formal interpretation of decades, right?

Recent legislation in the European Union does exactly that. In its standardization of population and housing census methodology for member states, the EU specifies that member nations run a census “every decade” on a “reference date” of their choosing. “The first reference year shall be 2011. […] Reference years shall fall during the beginning of every decade.”5 In other words, the 1 years begin the decades and therefore the EU implicitly takes up the Ordinal position.

For the United States in particular, it’s even in our Constitution to apportion Congressional representatives according to state populations counted “every subsequent Term of ten Years,” though the period of “decade” is not used. In the New York state constitution, however, not only is “decade” mentioned (also for apportionment of representatives), but its exact year bounds are explicitly clarified:

… if, in any decade, counting from and including that which begins with the year nineteen hundred thirty-one, such a readjustment or alteration is not made at the time above prescribed, it shall be made at a subsequent session occurring not later than the sixth year of such decade, meaning not later than nineteen hundred thirty-six, nineteen hundred forty-six, nineteen hundred fifty-six, and so on …6

Between the mention of 1931 as the beginning of a decade and the mention of 1936 as the sixth year of the decade, the New York constitution clearly takes the Ordinal position.

Back to the whole US, the legal language around the decennial census itself does not seem to mention “decade” anywhere, not in any historic iteration of the Census Act and, surprisingly, not in the US Code Title 13 that codifies the census bureaucracy. Our census occurs in the 0 years but there’s no qualification that these begin each decade. A 1908 American Statistical Association survey of census methodology across the Americas, however, sheds some light on the counting in this field:

The most generally accepted dates for a decennial census are those that begin or end decades. The tenth year of the decade has been accepted in the United States and in several European countries, and in Brazil. England and most of her colonies accept the first year of the decade.7

The US census occurs in the 0 years, referred to as the tenth (last) years of the decades, while the UK census occurs in the 1 years, referred to as the first years.

Altogether it seems that governments, at least those conducting decennial censuses in the anglophone world, take up the Ordinal position on decades.

The Historical Record

With the geek and wonk authorities taking contradictory positions on the decade question, what about popular usage in the archives of major newspapers and other such publications? A scattershot of archival records, generally by searching for "new decade", suggests that both counting styles have been used over the past century or so—and sometimes inconsistently in the same place. Such evidence includes:

- Ordinal: An article in Science tabulating a century-old bibliography of astronomy texts in 1906.8

- Cardinal: A report on a decennial medical conference in the 1876 Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of New York.9

- Cardinal: A New York Times article welcoming the new year — and decade — in 1860.10

- Both: An editorial about the state of international politics in 1930, using ordinals to describe the decade but beginning from 1930!11

- Ordinal: A swanky fundraiser called the “New Decade Mardi Gras and Ball” in January 1941, as reported by the New York Times.12

- Cardinal: A different, possibly less swanky fundraiser also called “New Decade” in December 1949, also reported by the New York Times.13

- Cardinal: A 1960 call for a new Renaissance of worldly experts, not just invoking “our new decade” but identifying three decades cardinally.14

- Cardinal: The inaugural speech of New York City Mayor John Lindsay on the last day of 1969.15

- Cardinal: A New Year message in the 1880 New York Tribune.16

- Ordinal: A look at the plays of “the new decade” in the 1890 New York Tribune, ten years later but with a different position.17

- Cardinal: A celebration of “holiday trade” in the 1889 Boston Globe.18

- Ordinal: A chest-beating celebration of the Chicago Tribune’s year ahead in 1921.19

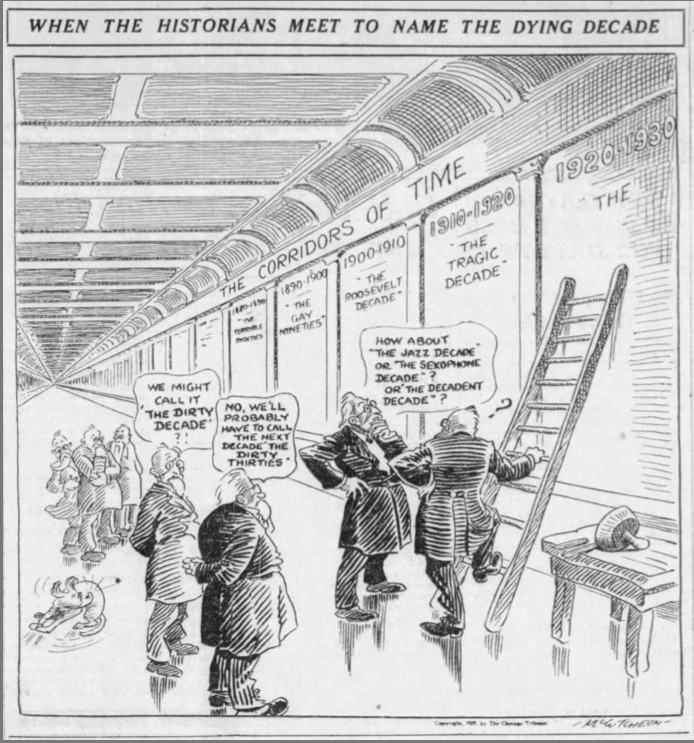

- Cardinal: A cartoon about historians naming “the dying decade” in the 1929 Chicago Tribune.20

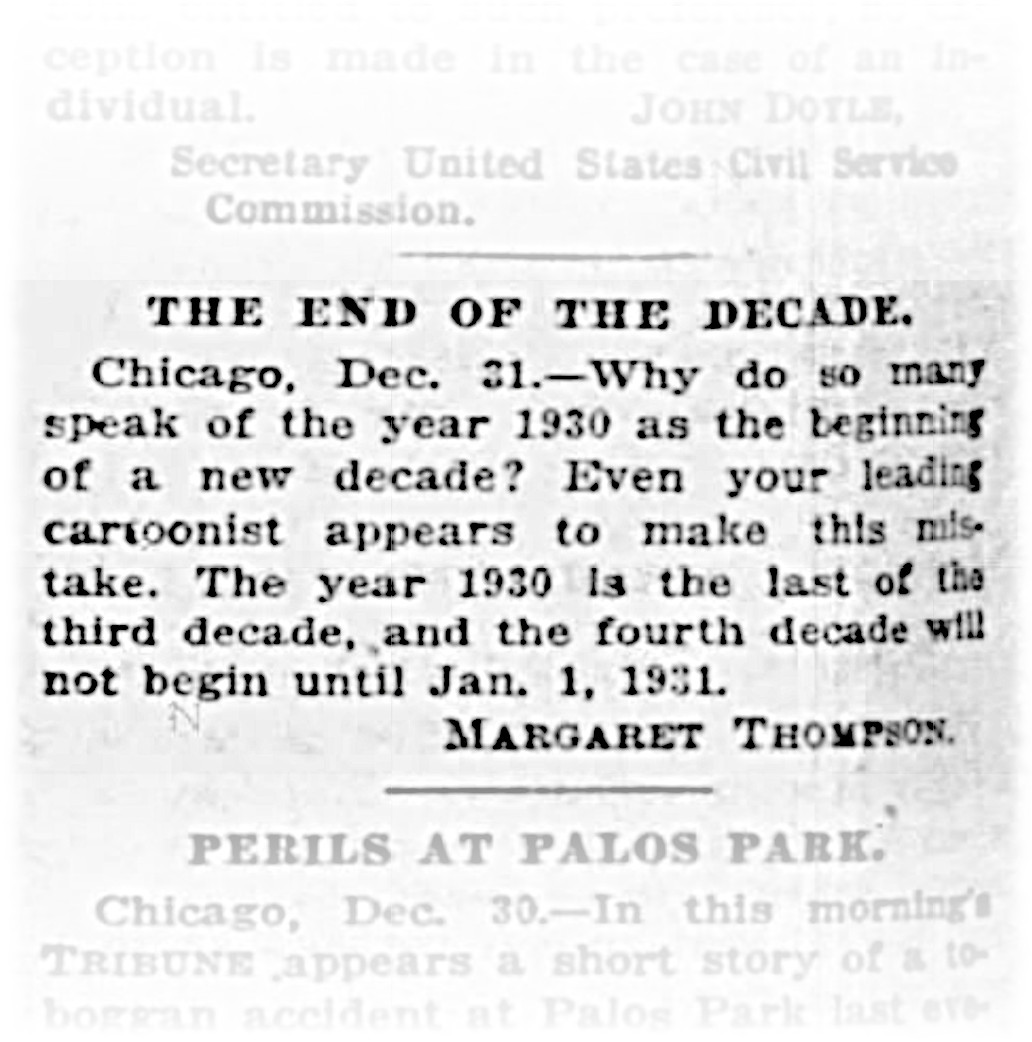

- Ordinal: An angry reader response to that cartoon’s mistake identifying the decade.21

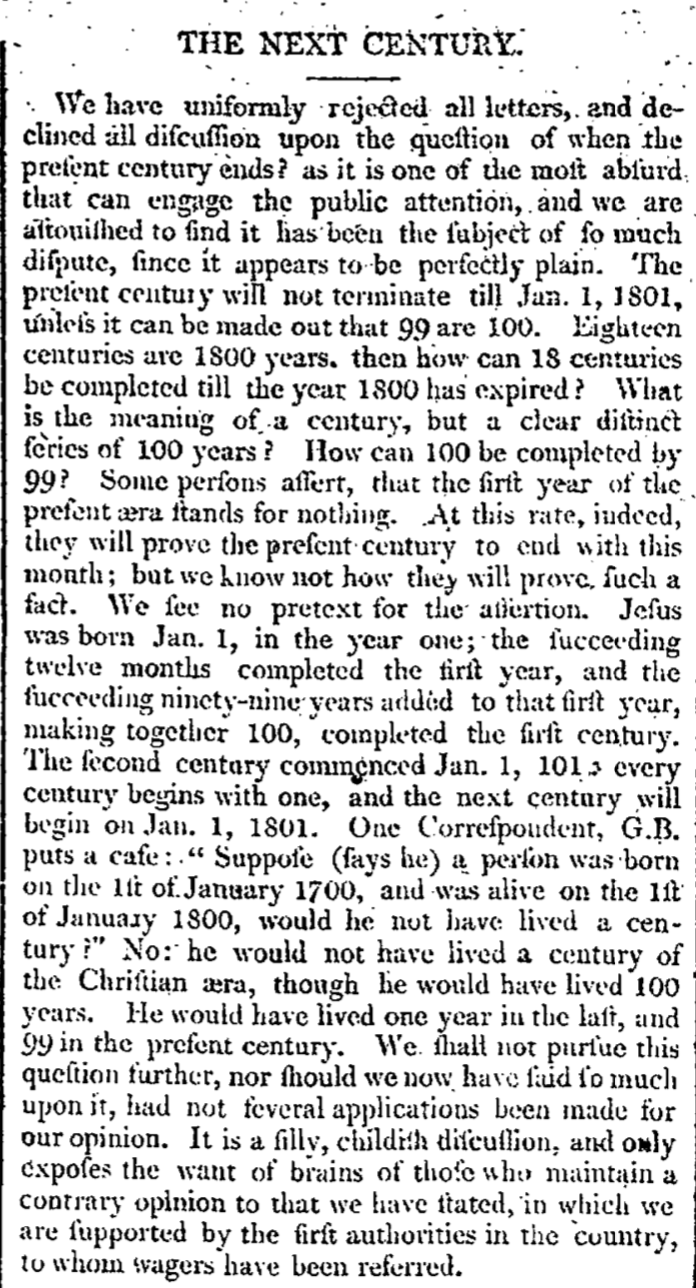

- Ordinal: An editorial response to a reader’s query about the start of the new century in 1900, linking it explicitly to the decade dilemma too, in the New York Tribune. The masterful response cites two encyclopedias’ entries on “Chronology,” explains the frustrated lack of astronomical year zero, provides multiple enumerations of years in decades, concurs with our philosophical Canadian hockey player Rielly on the multitude of decades available, and even cedes territory to the Cardinals on common expressions like “in the [eighteen!] sixties.”22

Whew. With all the discord around counting decades, how do we resolve the dilemma? To better equip ourselves with the tools to conclusively resolve it, we should first look to the century dilemma.

).](https://typesandtimes.net/assets/img/decade/nytribune-1900-spread-to-decades.png)

Centuries of History of Centuries

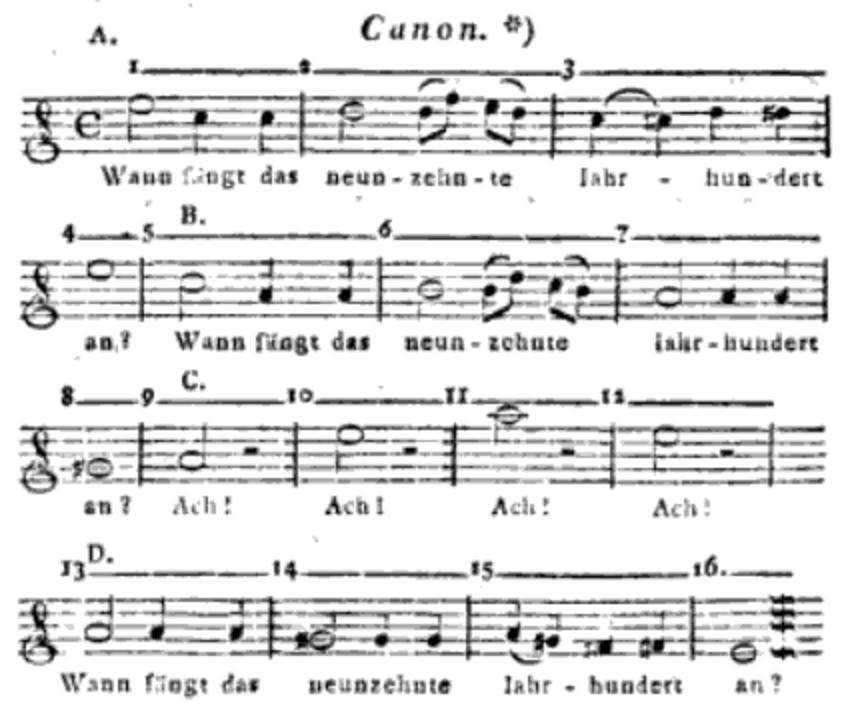

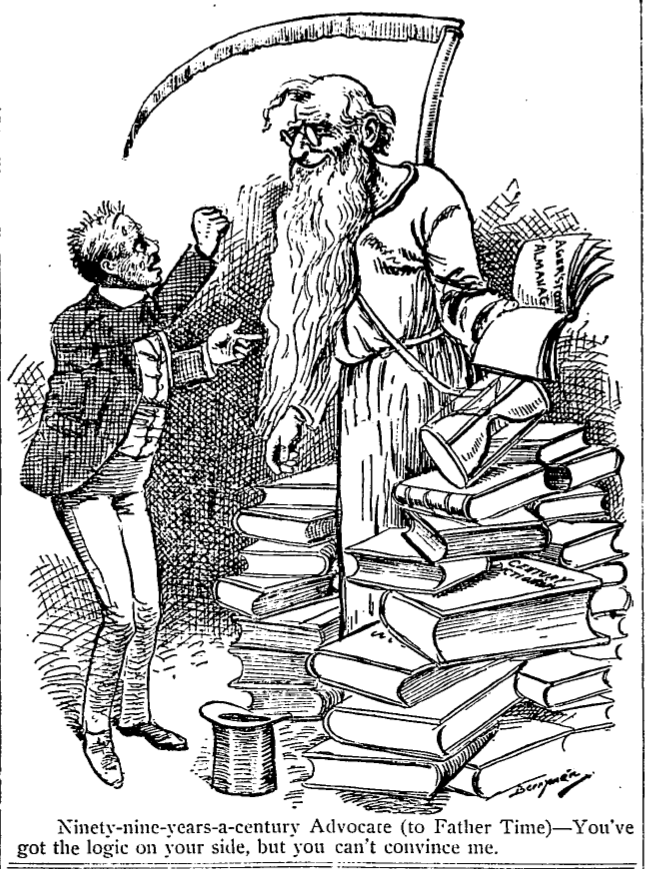

At the level of centuries, this debate has raged for… centuries, most notably the transition from 19th to 20th centuries. La fin de siècle, as it was known in France and in high culture, garnered tremendous attention worldwide. Philosophers, intellectuals, journalists, emperors, and popes all debated and ruled on the exact beginning of the 20th century, their efforts published for mass audiences in the world’s newspapers. In response, where today we have social media, back then they had letters to the editor.

To count centuries, the Cardinals would say that we’re in the 2000s, running from 2000 to 2099, and last we were in the 1900s, running from 1900 to 1999. Surely one cannot deny the legitimacy of referring to centuries as such. The Ordinals, on the other hand, would say that we’re in the the 21st century, running from 2001 to 2100, and last we were in the 20th century, running from 1901 to 2000.

Stephen Jay Gould deemed the debate to be one between “high culture” on one side — the scholarly mantle of Ordinals — and “vernacular culture” on the other — the common-sense laurels of Cardinals, most notably expressed in the 1890s.23 A century later, he remarks, it would be Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001 vs. Prince’s 1999.

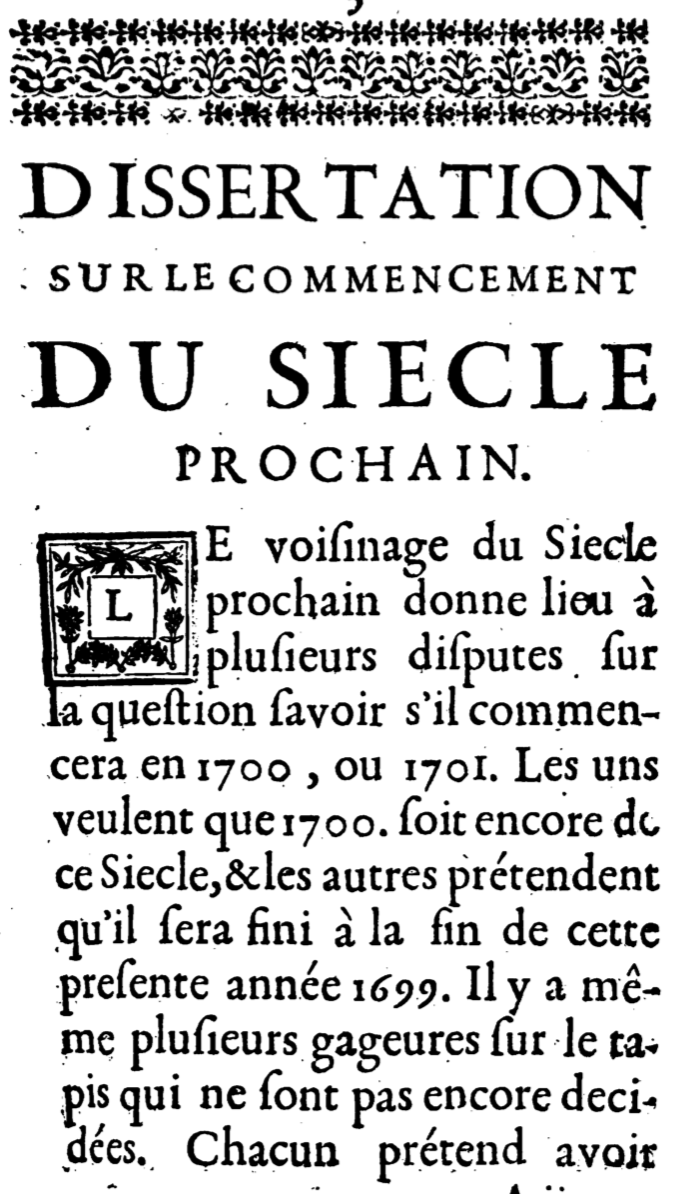

On the side of high culture, insisting that centuries begin in the 01 years, stood Pope Leo XIII,24 astronomers going back centuries,25 and many newspaper editors. They even recognized the distinction as one between cardinal and ordinal numbers, going back at least to 1699.26

On the side of vernacular culture, arguing for the 00 years, stood Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany,27 the Wellesley College president,28 and — most importantly — the common people. One such common person articulated his position on the “great secular event” of the turn of the century as a populist backlash to “the abacists”:

Shall we wait now a whole year for 1901, at the behest of the abacists? No, we will not pass over the significant year 1900, which is stamped with the great secular change, but with cheers we will welcome it and the new century. The 1900 men, who compose the vast majority of the people, say to their opponents: “We freely admit that the century you have in your mind, the artificial century, begins in 1901, but the natural century (which we prefer) begins in 1900.”29

Also in the Cardinals camp on the century question is, again, ISO 8601. It defines centuries analogously to how it defines decades.30

In the end, with the intelligentsia on their side the Ordinals won the debate on centuries, as long as the ordinally-specified phrase “the __th century” remains the common expression for centurial periods of history. Then do they also win the debate on decades?

What’s a Decade Anyway?

A millennium is grandiose. A century is once in a lifetime. But a decade? That’s pedestrian. Indeed, among these three periodizations of history, the decade stands alone as being primarily cultural in nature. “Decades are not a function of calendar time,” wrote Newsweek journalist Bill Barol. “They are trends, values, and associations, bundled up and tied together in the national memory.”31

Without the grandeur of a century, the decade question has prompted far less (serious) debate. The decade, as a periodization of history, is a fairly recent concept. In the 1940s historian Marc Bloch had already warned against the “insidious” practice of periodizing by centuries:

We no longer name ages after their heroes. We very prudently number them in sequence every hundred years, starting from a point fixed, once and for all, at the year 1 of the Christian era. […] Unfortunately, no law of history enjoins that only those years whose dates end with the figures ‘01’ coincide with the critical points of human evolution.32

If centurial thinking already had “no rational basis,” what about the decade? Warren Susman criticized it as “a special and perhaps characteristically American way of seeing the past: as a series of decades that fit neatly into limits imposed by man-made calendars.”33 Jason Scott Smith, in his 1997 article “The Strange History of the Decade,” traces the history of the decade in primarily American, primarily cultural thought.34 “The decade contributes to an abbreviated historical attention span—cause and effect are confused, and the record of the past is reduced to a ‘progression of cultural styles.’” When did this begin? According to Smith, oweing to the World War, to global revolutions of technology and politics, and to a subsequent decade full of nostalgia, the 1920s were “the first decade truly to legitimate a ten-year span of time as a historic category.”

This difference in the idea of the decade, as compared to centuries, also matches the common language to talk about them. Here, the Cardinals have the advantage: you’re far less likely to hear talk of “the 203rd decade” than “the 2020s.” The situation is reversed for centuries: “the 21st century” is more common than “the 2000s.” While it’s not immediately clear how to search for “the __s” vs. either “the __ century” or “the __ decade,” we can at least compare the frequency of the ordinal reference to “centuries” vs. to “decades,” shown by the Google Ngram Viewer results below.

showing frequency of ordinal reference to centuries vs. to decades.](https://typesandtimes.net/assets/img/decade/ngram-results-ordinals.png)

Taking the cardinal invocation of decades to be far more common than the ordinal invocation, it seems to me that the Cardinals win the decade debate. And although this is the opposite of century counting, the distinction in the concept of the decade seems to further warrant the distinction in counting.

Conclusion

In this article I’ve argued decades begin on 0 but centuries begin on 01. (How sorry I am to disagree with the ISO 8601 standard in the latter case.) Of course, disregarding a chronological epoch like the year 1 C.E., decades are also just arbitrary spans of ten years of time.

Have we now begun a new decade, the 2020s? I argue yes, while others would argue no. The only certainty is that, like the century debate, the question will never quite die; it will circle back around every decade. “DISCUSSION ALWAYS RECURS,” one 1900 headline reminds us.35 But if each time we can piece together a bit more perspective, culturally and historically, we might finally be equipped to solve it for good.

Or maybe the common people will simply overpower the abacists.

-

In terms of the ISO 8601 standard, introduced later in this article, the decade as a mere span of ten years is a time interval of duration ten years. Above, Rielly gives two examples of such time intervals:

2008/2017and2009/2018, both valid time intervals of year precision according to ISO 8601, and also expressible as2008/P10Yand2019/P10Yrespectively. Or they could be ten-year time intervals at minute granularity, e.g.,2009-12-31T14:30/P10Yas the decade beginning at 2:30 pm on 31 December 2009 and ending at 2:30 pm on 31 December 2019. ↩ -

For the reinterpreted definition of the Gregorian calendar, see ISO 8601-1:2019, Section 4.2.1. A draft copy of an older version exists on a web server for the Library of Congress; Section 3.2.1 there. The Java library for date and time —

java.timeor JSR 310, one of my all-time favorite APIs — describes the ISO calendar system as “the de facto world calendar.” ↩ -

Virtually every discussion of the century debate includes mention of the absence of year zero in the Gregorian calendar (often called “the astronomical year zero”). See Gould for a discussion of the creation of Anno Domini by the monk “Dennis.” “In short, Dennis did not begin time at zero, thus discombobulating our usual notions of counting. During the year that Jesus was one year old, the time system that supposedly started with his birth was two years old. (Babies are zero years old until their first birthday; modern time was already one year old at its inception.)” There’s also a particularly expansive discussion of this history in The Boston Herald. ↩

-

For the definition of decades, see ISO 8601-1:2019, Section 4.3.11, and extended definitions in Part 2, ISO 8601-2:2019, Sections 4.3.5 and 4.4.1.7. ↩

-

“Regulation (EC) No. 763/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 July 2008 on population and housing censuses,” Article 5, Paragraph 1 (“Data transmission”), pp. 115 of linked document. ↩

-

New York State Constitution, Article III, Section 4. ↩

-

S. N. D. North, “Uniformity and Co-Operation in the Census Methods of the Republics of the American Continent.” Publications of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 11, No. 84, December 1908, pp. 301. ↩

-

Edward S. Holden, “A Summary of the Bibliographie Astronomique of Lalande for the Years A.D. 130 to 1473, the Epoch at Which Scientific Books Began To Be Printed,” Science, New Series Vol. 23, No. 588, pp. 548. Holden tabulates the bibliographic data from Lalande, reproducing Lalande’s (conventional) usage of ordinals for centuries; he also appears to give his own ordinal description of the decades within each century. ↩

-

E. R. Squibb, “Report of Dr ER Squibb as Delegate to The American Medical Association on the US Pharmacopoeia,” Transactions of the Medical Society of the State of New York, 1876, pp. 199. The US Pharmacopoeia is a decennial conference occuring in the

0years. Squibb mentions that the conventions are held on “the first year of the new decade.” ↩ -

“A Happy New Year,” New York Times, 2 January 1860, pp. 5. “The birthday of 1860, the commencement of a new decade, will not, we may fully anticipate, fall behind those of previous years, which have now joined the antediluvian era, to which the poet makes reference.” ↩

-

“Towering Problems of the New Decade,” New York Times, 27 April 1930, pp. 83. “As the fourth decade of the twentieth century opens […] What are likely to be the dominant trends of the decade just beginning?” ↩

-

“New Decade Dance to be Held Tonight,” New York Times, 30 January 1941, pp. 24. ↩

-

“New Decade Dance to be Held Dec. 11,” New York Times, 13 November 1949, pp. 87. ↩

-

“The Kind of Expert Our New Decade Needs,” New York Times, 2 January 1960, pp. 12. The article invokes “the Forties” as “the Atomic Decade,” “the Fifties” as “[the] Lunik [decade],” and “the Sixties” as “the Decade of the Experts.” ↩

-

“Text of the Lindsay Inaugural Speech,” New York Times, 1 January 1970, pp. 15. The speech was delivered on 31 December 1969 opens with the statement that “[t]his is the last day of the decade.” ↩

-

“Progress,” New York Tribune, 1 January 1880, pp. 4. “A new decade begins.” ↩

-

“Plays of Ninety-One,” New York Tribune, 28 December 1890, pp. 19. The dek: “How the New Decade Will Begin at the Theatres.” ↩

-

“The Holiday Month,” Boston Globe, 1 December 1889, pp. 12. Mentions “the new decade that starts with 1890.” ↩

-

“1921 Will Reward Fighters,” Chicago Tribune, 3 January 1921, pp. 34. “A new year, a new decade, a new epoch open before us.” ↩

-

“When the Historians Meets to Name the Dying Decade,” Chicago Tribune, 29 December 1929, pp. 1. See the embedded image in this article. ↩

-

“The End of the Decade,” Chicago Tribune, 4 January 1930, pp. 10. A reader’s frustrated rejection of the political cartoon published a week before. “Even your leading cartoonist appears to make this mistake. The year 1930 is the last of the third decade, and the fourth decade will not begin until Jan. 1, 1931.” See the embedded image in this article. ↩

-

“The End of the Century,” New York Tribune, 23 December 1900, p. 16. Saved to pdf for posterity here. This article is dear to me because of its detail, clear language, and scholarly aspirations. The editor begins by praising the letter, which is “truly a comfort”; it’s “plain, straightforward, candid, modest and honest.” “If [the letter’s author] could see the letters on this subject which have been received at this office in the last week, the most of them stupid and silly, some of them abusive and all of them except his anonymous, he would blush for his side of the case.” Regarding the Cardinal approach to naming and counting decades: “But it is merely a loose and conversational mode of speech, like many another. It has no historic or mathematical significance, and has nothing to do with the question.” Regarding the decade as a mere time span: “It must be borne of mind, however, that the word ‘decade’ means merely a period of ten years, regardless of when it begins or ends. The period from July 4, 1876, to July 4, 1886, is just as much a decade as any other period of ten years.” ↩

-

Stephen Jay Gould, Questioning the Millennium, 1997, Part 2. ↩

-

The scholarly Pope Leo XIII issued an address on 13 November 1899 clarifying that “at midnight of the last day of December of the coming year [1900] the present century will come to an end.” It was reported in various US newspapers, notably cited in “Is the Twentieth Century Here, Or Is It Not?”, Literary Digest, Vol 19, No 27, p. 798. ↩

-

For an extensive list of scholarly debate about when centuries begin and end, see “The Battle of the Centuries,” an extensive bibliography compiled by Senior Science Specialist Ruth Freitag at the Library of Congress. ↩

-

De Laisement, “Dissertation sur le commencement du siècle prochain et de la solution du problème scavoir laquelle des deux années 1700 ou 1701 et la première du siècle,” 1699. On page 9 he introduces the distinction between cardinal and ordinal numbers. ↩

-

An account of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s erroneous declaration of 1900 as the start of the century, from Bode’s “Liminal Projections: Utopian and Apocalyptic Visions, 1790s : 1990s”:

Reichskanzler Fürst zu Hohenlohe-Schillingfürst asked his majesty Kaiser Wilhelm II in a telegram [dated 4 December 1899] most submissively to decide when the beginning of the new century was to be celebrated, ‘allerunterhänigst um Entscheidung’ [‘wholeheartedly for a decision’], ‘wann der Beginn des neuen Jahrhunderts zu feiern ist’ [‘when to celebrate the beginning of the new century’]. The Kaiser declared it should be in 1900 and few of his subjects dared object, though pockets of resistance were reported from Bavaria.

The Kaiser’s response: “am 1. Januar 1899,” a telegraphic typo according to Richard Kämmerlings in the German FAZ newspaper. ↩

-

At the end of 1899 the Boston Herald asked an array of college presidents to conclusivey determine the year that begins the 20th century. In the December 10th issue they published the results in a huge spread, along with a history of calendar systems. Colleges whose presidents or other professors correctly said 1901: Princeton, Cornell, Columbia, Penn, Vassar, Bowdoin, Dartmouth, Brown, Yale, Harvard, and Chicago. Those who incorrectly answered 1900: Wellesley, Tufts, and Smith. Elsewhere the New York Tribune editor writes of the 1900 error: “This notion has about disappeared, however, before the gaze of calm eyed mathematics. The only persons of prominence who ever held it were the president of Wellesley College and the German Emperor” (12 December 1899, “La Fin de Siecle,” pg. 6). ↩

-

Neal H. Ewing, quoted in “The Natural Century,” The American Architect and Building News, Volume 65, 1899, pg. 62. ↩

-

For the definition of centuries, see ISO 8601-1:2019, Section 4.3.12, and extended definitions in Part 2, ISO 8601-2:2019, Sections 4.3.6 and 4.4.1.8. For example, the 21st century, “the 2000s,” is represented as

20C, and like with decades, there are zero (0C) and negative zero (-0C) centuries that both contain year 0. ↩ -

Bill Barol, “The Eighties Are Over,” Newsweek, 4 Jan 1988, pp. 40-41. ↩

-

Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, 1944, pp. 181-182. Another passage from this book that’s particularly relevant for those of us interested in the time zone database (tzdb):

Now, the scholar loves close dating. He finds it both an appeasement to his instinctive horror of the vague and a great comfort to the conscience. He wants to have read and to have checked everything which concerns his subject. […] However, let us beware of worshipping the idol of false precision. The most precise measurement is not necessarily the one which refers to the smallest unit of time—in which case, we should have to prefer not only a year to a decade, but also a second to a day—it is the one which is best adapted to the nature of the events.

-

Warren Susman, Culture as History, 1973. ↩

-

Jason Scott Smith. “The Strange History of the Decade: Modernity, Nostalgia, and the Perils of Periodization.” Journal of Social History, vol. 32, no. 2, 1998. All of the discussion about the particularity of the decade above comes from this fascinating article! ↩

-

“Century Not Ended Says Flammarion,” The Nashville American, 4 January 1900. Headline and dek reproduced in third image embedded above. A reasonably authoritative account of the Ordinal position on centuries, from a French astronomer Camille Flammarion, loaded with history and even literal French citations. ↩